From Bathhouse to Boiler Rooms, inside the rise of sauna raves.

It’s getting hotter and hotter in here, and everyone’s already taken off their clothes. Over the pulse of deep, rolling techno my friend leans in and says, “This could be a darkroom”.

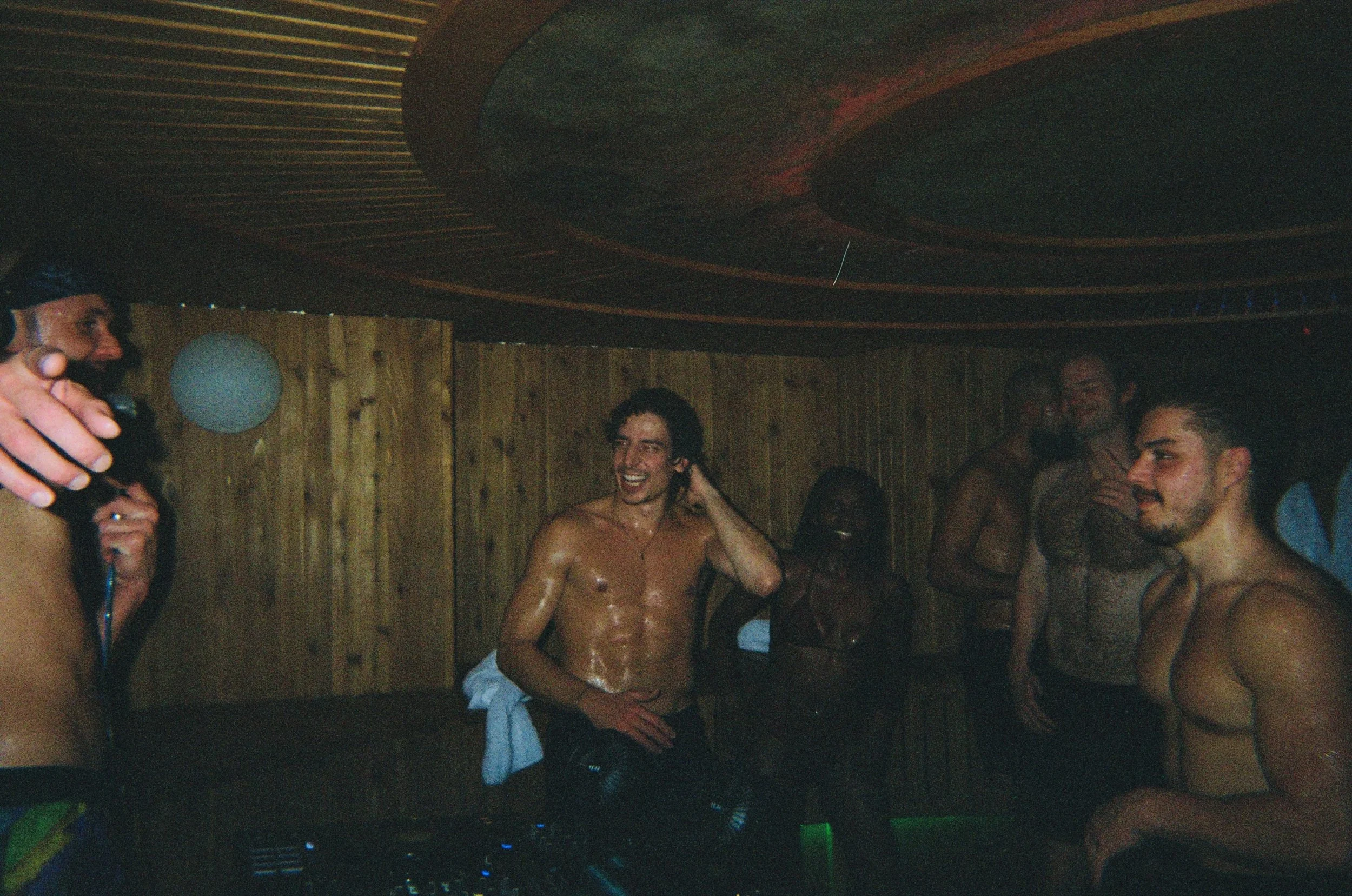

We’re at a rave inside a sauna—forty people dancing to a proper soundsystem in a coal-fired room at &Soul’s new “wellness house”, The Sanctuary in Shoreditch. Home to the first sauna rave in London, or so they claim. The coals hiss as water is ladled over them. Steam rises in thick clouds. Sweat drips from elbows, collarbones, eyelashes, down to the dance floor.

I have never been this close to so many other people this scantily clad, moist and sober. And yet, despite the heat and the bodies, the atmosphere feels unexpectedly relaxed. No-one is leering or shoving for space. People move with care, checking in with glances, shifting to make room. I feel held, like I’m participating in a ceremony.

Back in the changing rooms, faces flushed and hair plastered to our skin, I struggle to open my locker. “Don’t worry it’s normal”, the woman next to me reassures me. “You probably have sauna brain, it’s happened to me countless times”. I ask her, “Is this really the first sauna rave ever?” She smiles the way adults smile at children when they’re being earnest. “Put it this way,” she replied, “I’m fifty and I’ve been going to sauna raves since my twenties”.

In various forms, communal sweating has existed on British soil for thousands of years. In a rather dramatic introduction to their history of British sauna culture, British Sauna Society claims, “Before the Romans, before the Celts—even before written language—there was sweat”. Archaeologists have even uncovered the remains of what they believed to be Bronze Age saunas, off the coast of Scotland and near Stonehenge, evidence of ritual gathering in sweat lodges.

What’s new isn’t saunas themselves, but their return as a social space—we're in the midst of a sauna renaissance, if you will. In 2023 the UK had 43 saunas. Today, there are over 200. “Saunas are appearing where we need them most: at the edges of the sea, in the cracks of the city, in gardens, on farms, in disused shipping containers and artist residencies”, says the British Sauna Society.

The concept of saunas has been creatively reinvented, today they’re some of the UK’s hottest music venues. In Peckham, there is Sauna Social Club, the area's “coolest hangout spot”, where live DJs soundtrack your sauna with ambient sets. In Brighton the horsebox sauna Beach Box was so popular during the Fringe Festival it never left. On the Isle of Wight, Camp Bestival founders are on a mission to turn England’s largest island into a “sauna island” with their ever-expanding pop-up, Slomo Sauna.

And the pretty lady is right. In fact, sauna raves have helped shape the club culture we know today. One of the most notorious clubs in 1960s New York City was the Continental Bathhouse. During a time when homosexuality was criminalised, the Baths were an important social space for gay men; they could meet, swim, relax and even have sex. However, as the popularity grew, founder Steve Ostrow started booking entertainment. In a recent interview with the Guardian, Ostrow recounts seeing Mick Jagger, Andy Warhol and Alfred Hitchcock taking in shows. Within a decade, all the biggest names in the city had played there.

The Baths are a lesser-known cornerstone of dance music history. One of the first ever stages designed specifically for DJ sets was built for this venue. Some of you may know DJs like Levan and Knuckles, both of whom started their careers by earning twenty-five bucks an hour playing here. Levan would later become resident at the legendary Paradise Garage in Manhattan, and Knuckles would move to the Warehouse venue in Chicago, where he helped develop the sound of house music.

However, the sauna rave we went to was not that kind of sauna rave. I may have misled the friend I brought. Pretty soon into the rave he realised that he’s the only one in speedos—“a sign”, he claims, that he’s “invaded straight territory”. It's been a while since he’s tried to chat up a straight man, and he was feeling rusty.

But that’s not the only way in which the party differed from the hedonism at The Baths. Here, there was no danger of anyone lacing our drinks with LSD, because this was a sober rave, meaning no substances, not even alcohol allowed. Around the world we’re seeing a surge in sober parties as people look for new ways to dance and connect without drinking. Earlier that week, Mel C—Sporty Spice herself—played a boiler room set in a sauna in New York. This was organised by Daybreaker, self-labeled community architects, whose sober morning sauna raves are now a relatively socially acceptable way to start your day in NYC and LA.

Ordering a non-alcoholic Guinness at the pub doesn’t even raise an eyebrow anymore. These days, over a quarter of adults in the UK don’t drink at all. Clubs that once relied on bar sales are being forced to rethink their models, while daytime events and substance-free spaces are multiplying. The night out is changing.

This all raises a bigger question: what does the collision of wellness culture and underground dance music mean for nightlife? Is it a sign that club culture is healing or that we live in dystopian times—when everything from joy to community must be monetised?

My friend and I came of age in a time where parties didn’t start till midnight and substance abuse was socially prescribed. And yet here we are: stone-cold sober and dancing. Twenty minutes into the sauna rave and there’s already a dance circle. People who have never met are slipping on the wet floor, getting low, and laughing as they catch each other for balance.

Despite some initial cynicism, I think we might be genuinely having fun and connecting to others. It’s mortifying how easy it feels. Everyone here is so unflinchingly friendly. I’m told that the DJ also runs a men's talking therapy group. I haven’t talked to this many strangers in a while. In fact, I’m shocked I have the confidence to talk to anyone new while half-naked and sweating.

Another difference about this party is how comfortable I feel in my body. Yes, most people in the room look like yoga teachers, but I don’t feel judged. Maybe it’s knowledge that no-one (except our photographer) is supposed to take photos. Or once you’re in a swimming costume sweating through the heat, there’s no point trying to serve a look; any make-up would just melt anyways. In a world where heading to the club can feel like going to a livestock show judged by mean girls, this feels freeing.

Of course, it wouldn’t be a real party if you didn’t bump into someone you know. A friend I haven’t seen in a while calls my name, excited, and drags me outside to do a cold plunge. The plunge area looks like a sci-fi set, metal tubs glowing with neon temperature displays. I’ve opted for a relatively humane 9 degrees Celsius, he opts for 5 degrees. We both scream as we lower ourselves in.

“Keep talking to me” he yells, squatting in the tub. After the initial shock, the pain dissolves into a loose buzzing calm. “I feel like I’m on drugs”, he says, eyes wide, thumping his chest. “You know when your heart is racing, just beating, like - DUM DUM DUM”. He’s not lying. He hasn’t taken anything. The body, it seems, has its own chemistry.

Harbinger of the sauna revolution, the non-profit Community Sauna Baths have converted a whole new generation to the benefits of getting sweaty through their affordable sauna sessions. Their flagship venue, The Bath House, is a place where sauna bleeds into social life, they have ecstatic dances, chess tournaments, life drawing, and even a choir. The travelling soundsystem Giant Steps have even hosted legendary Floating Points there. In the past couple of years, the growing demand for sauna has led them to expand across more locations, from Hackney Wick to Walthamstow, Camberwell and Stratford.

In June this year, The Bath House was at risk of closing down after Hackney Council moved to terminate their lease of the former 1930s Bath House. Thousands mobilised in protest, signing petitions and sharing testimonies about what the space meant to them. “This is a sacred space”, one person wrote, “My grandad used to bathe here when he was a kid growing up in East London during the war, and now I dance here” Another described it as “essential for mental health and bonding". By October, The Bath House had won - the Council announced that they had permission to take over the management of the site.

Over the past few decades, third spaces—from nightclubs and music venues, to libraries and community centres—have faced a deliberate and sustained attack. Rising rents, licensing laws, funding cuts, and digital substitution have thinned out the places where people can gather. Modern life is more atomised than ever, the promises of social media to keep us more connected have fallen short. In an era where parties have been replaced by networking events and brand activations, the rise of saunas is a welcome intervention. The sauna renaissance feels like a return to something older; spaces that require physical presence, vulnerability and participation.

As I step back into the heat, skin still tingling from the plunge, bass thudding through the walls, I think of how this feels familiar rather than like a new trend. Like the best underground raves, there is an unspoken social agreement - to look after each other and commit fully to letting loose and letting go. We’ve always gathered like this. Raves don’t need clubs or alcohol. They just need some heat, sound, and bodies to sweat.

Written by Trà My

Edited by Sophie Yau Billington

Photography by Annabelle King