Is it Finally Time to Leave Spotify?

Following the announcement of Spotify CEO Daniel Ek’s €600 million investment in AI defence technology, we catch up with the founders of the ‘new-age’ music platform Nina Protocol to discuss what an alternative future for streaming might look like.

Daniel Ek isn’t a well-liked figure in the music world. When news broke in June that he had once again led an investment round into the AI defence company Helsing, contempt for the Swedish billionaire and his platform boiled over. His decision to double down on the German tech firm while the destructive power of surveillance technology is being laid bare in places like Gaza and Ukraine deepened long-standing doubts about the ethics of the streaming giant. For many, it has renewed a sense of urgency to the question: Is it finally time to leave Spotify?

In the last decade, Ek’s once carefully curated image as a passionate music lover has all but disappeared. Criticisms of his claims that the “cost of creating content” (Ek’s preferred term for what you or I might call music) is “close to zero”, to his dismissal of a potential Spotify boycott, have been constant. Throughout, Ek has made clear that the recent wave of artists leaving the platform is, to him, little more than a blip in the ever-upward march of his empire.

Spotify’s disregard for artists is baked into the platform itself. Its one-size-fits-all streamshare model funnels revenue upward, enriching global megastars and major labels while leaving independent artists to fight for scraps. Success in the streaming economy requires conforming to the norms of pop stardom, with only records engineered for mass-scale success able to break through the fog of algorithmic mysticism - a vision many artists never aspire to in the first place.

Author Liz Pelly pushed the streaming debate into new territory and laid out its systemic issues with piercing clarity. Mood Machine, the culmination of her decade-long reporting on the inner workings of Spotify, detailed the numerous exploitative practices the company has used to cut costs and boost engagement. Among its most damning revelations was Spotify’s use of so-called ‘ghost artists’: tracks commissioned by the platform and released under fabricated profiles to quietly pad mood-based playlists. Already undervalued by the system, artists now saw their limited revenue siphoned off in favour of platform-owned stock music.

Ghost artists weren’t the only way Spotify was manipulating programming for its own advantage. One of its most successful schemes was ‘Discover Weekly’, which offers independent artists the opportunity of algorithmic promotion in exchange for lowered royalty rates. The currency was exposure - a deal that many artists, without the backing of major label representatives pitching for playlist inclusions, felt they had little choice but to accept. What makes this trade-off more unfortunate is that extra streams rarely grow into the kind of real support that sustains a career: people at shows, buyers of records, or fans who actually care.

For listeners the convenience of streaming is starting to lose its appeal, with users frustrated at how little control they now feel over their own musical choices. Recommendation systems, presented as tools to guide discovery, have instead nudged listeners into passive listening habits: a way of managing abundance rather than deepening engagement. Faced with a seemingly endless catalogue and no real reason to select one track over another, listeners not only accept the algorithm’s authority but begin to rely on it, making walking away from these platforms all the more difficult.

Most alternative ways to consume music online can feel too similar to Spotify. One that truly stands apart is Nina Protocol, a direct-to-fan sales platform and discovery hub where artists keep 100% of their revenue. Unlike the retention-driven logic of big streaming, Nina’s approach recalls the energy of the DIY blog era: context-rich, community-driven, and fuelled by enthusiasm rather than extraction. In doing so, Nina has emerged as a vital space for discovering and supporting independent music. To understand how it works, and how the team hopes to modestly rewrite the rules of streaming, we spoke with its founders, Mike Pollard, Eric Farber and Jack Callahan.

Nina Protocol logo

In an interview back in 2022, you [Eric] suggested that we were “at the precipice of a renaissance rather than in a dark age” when it comes to the state of our digital music ecosystem. In the 3 years that have passed since, where do you think we stand now?

Nina: I think the “renaissance” I was hoping for in 2022 was to see musicians forge new paths for themselves and I believe we are seeing that to a degree. It feels like independent music is a formidable force right now - people are leaving big DSPs, artists and listeners are seeking models different from the status quo. I think 2022 was actually the precipice of change, and three years later, we’re starting to see that change take shape.

Most importantly, as someone who hears a huge amount of music uploaded to Nina every day, I can say music itself is in a healthy place. It is incredible how much cool work is coming out across genres and geographies. The kids are alright.

When setting out to build Nina, I’ve seen that one of the main aims was to design a platform that emulates real music scenes, both in how music is created and how it’s discovered by audiences. In what ways does this differentiate Nina from conventional big streaming (DSP) models?

Nina: When we look at Big Streaming, we see a handful of design choices that do not match how music communities actually function. One-size-fits-all monetisation, no real context or practical social elements, and a system that treats all listeners as identical, flattening the experience for both artists and audiences.

Nina was built to go the other direction. We give artists tools to control and experiment with how they price and present their music. Some artists have small, devoted fan bases, while others attract larger groups of casual listeners. It is not our role to prescribe how they should engage with either group. The goal is to give artists fair ways to monetise their work on their own terms.

On the discovery side, we emphasise what we call horizontal discovery. A listener can move through an artist’s hub to see their collaborators, label, and related releases, building a richer picture of how music connects. On the listener side, we have features like Top Supporters, which highlight an artist’s most engaged fans, and Bonus Material, which lets artists include additional media exclusively for buyers. These kinds of features are designed to bring context and community back into the music experience, allowing artists to connect more deeply with the people who care about their work.

The concept of blockchain still raises some suspicion among many people due to its association with crypto and the shadowy realm of NFTs. In the simplest terms possible, can you tell us how this technology is being used to enhance the autonomy of artists?

Nina: We understand the skepticism around blockchain. Most people encounter the technology through headlines about speculation, hype, or outright scams, and artists in particular have every reason to be wary. Over the last century, nearly every new technology from bootlegging, to pirating, to streaming has been a double edge sword - making music more accessible but at the same time making it harder for artists to get paid. That history is front of mind for us.

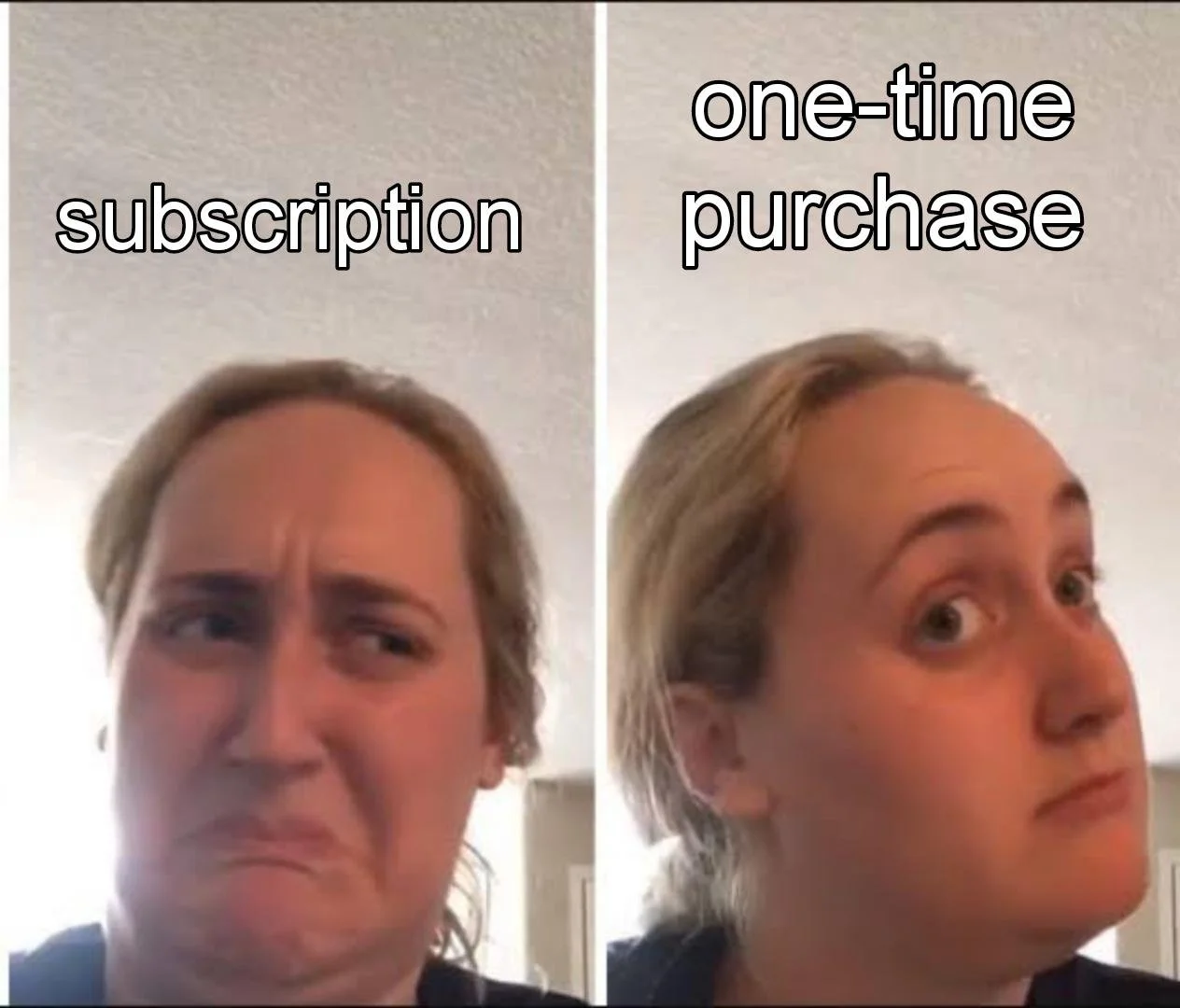

We view the blockchain banally as enabling a new kind of platform economics. One where artists get paid instantly anywhere in the world. One where artists don’t have to pay a monthly subscription to keep their catalog online. One where supporters can be recognized and rewarded for their support.

On Nina everything is priced in US dollars and there is no speculation or get rich quick promises that you see with NFTs. Most users pay with credit or debit cards, Apple Pay, or Google Pay. Artists receive payouts in fiat currency, not crypto. From the end user’s perspective, the experience is the same as any other site.

Can you tell us a bit more about the ‘community revenue shares model’? How does that work and what was the idea behind it?

Nina: The idea came from looking at how music scenes actually work. In real life, artists often build their careers through the support of friends and small networks of people who share their work. We wanted to translate that dynamic into the online space in a way that is simple, transparent, and built into the platform itself.

The community revenue shares model is our way of acknowledging and rewarding the role that curators, fans, writers and listeners play in helping independent musicians find their audience, in a world that often feels like outcomes are determined by algorithmic chance. Every time a release is purchased, the artist keeps 100 per cent of their sale price. On top of that, a small additional fee is added. Half of that fee goes to Nina, and the remainder is automatically distributed to different participants: the person who shared the release, the person who invited the buyer to Nina, the first purchaser who paid for the music’s storage, and the person who invited the artist to Nina.

Our goal is not necessarily to make anyone life-changing money from sharing music. Instead, we hope to present the beginning of a new model for platform monetisation that recognises the roles everyone plays and gets people more excited to rep their favourite music.

It was recently announced that the renowned archival record label Numero has brought its catalogue to Nina, who now joins the company of the likes of Hyperdub, Stroom, and AD 93. How do you go about selecting and approaching labels/artists to join the protocol?

Nina: In the early days, it wasn’t easy. We reached out to every friend and label we had personal ties with. Since everyone on the team comes from a slightly different corner of independent music, we were able to cover a wide surface and bring a couple of hundred artists and labels on board.

Hyperdub and RVNG were among the first established labels to embrace the platform, and we will always be grateful for their willingness to take a chance on us. Soon after, AD93, Stroom, and countless other incredible labels from around the world started to join. On the artist side, people like AceMo, dBridge, and Surgeon were early to see Nina as a way to release music in new and different ways.

Today, partnerships often happen very organically. Independent music is such a close-knit space that many labels are just one step away, often introduced to us through friends or peers already on Nina. Sometimes it’s even more spontaneous. When a label like Numero Group or Polyvinyl appears in our release feed without any prior conversations, we reach out to connect, hop on a call, and learn what they hope to get out of the platform. More often than not, there is a lot of common ground in those conversations, and we gather insights that help us make Nina better.

As artists and label owners ourselves, we are careful not to pressure small independents, but Nina only works if enough people are willing to take the leap. That leap is now happening at what feels like a remarkable pace.

One of the most disorienting features of the streaming experience is how little context is provided to the music that is algorithmically fed to us. This appears to be a major point of contrast to the approach at Nina, where various editorial series offer listeners more meaningful discovery routes. How important do you think re-contextualisation is in creating a better streaming ecosystem?

Nina: For us, context is everything. We often say that context is the difference between liking a song and loving an artist. In today’s media landscape, where listeners are overwhelmed with constant streams of content, it can be hard to remember much about any single song. Adding context helps anchor that experience. Who is the artist? What influences their music? Who do they collaborate with? What label are they on? These touchpoints make it easier for listeners to connect in a lasting way.

That’s why we put a lot of energy into editorial. Our written and video pieces are designed to share artist stories so that listeners have a more memorable experience at the moment of discovery. We believe this matters for artists, and it is something that is happening less and less through traditional channels

As Nina grows, we want to take the editorial tools we have developed internally and open them up so that artists, labels, and curators themselves can build and share context around their work. The goal is to create a powerful channel for elevating the voices that give independent music its depth and meaning.

On your about us page, it says that “Nina exists to empower independent music, artists and scenes at scale”. Do you ever worry about the effects that growth and scaling up might have on these aims?

Nina: It is less a worry than a consideration. We want to grow in a way that serves the interests of more artists and more communities of listeners, but that requires time and a measured approach.

We often look to sites like Discogs, YouTube, and Wikipedia as examples. They hold an encyclopedic amount of media, but they also help you quickly situate yourself in front of what is most relevant. That is the kind of balance we want to strike with Nina. Through horizontal discovery features, we aim to provide people with clear entry points into Nina, while still leaving room for the serendipity of stumbling upon something new.

That is the type of approach we want to maintain as we continue to grow.

Thank you for talking to us, Nina Protocol!

Take a look at Nina Protocol here.

Written by Jack Oakes

Edited by Zak Hardy