‘The air was thick with tension’: How Manchester’s Reggae and Dub Sound System Pioneers Broke Prejudice

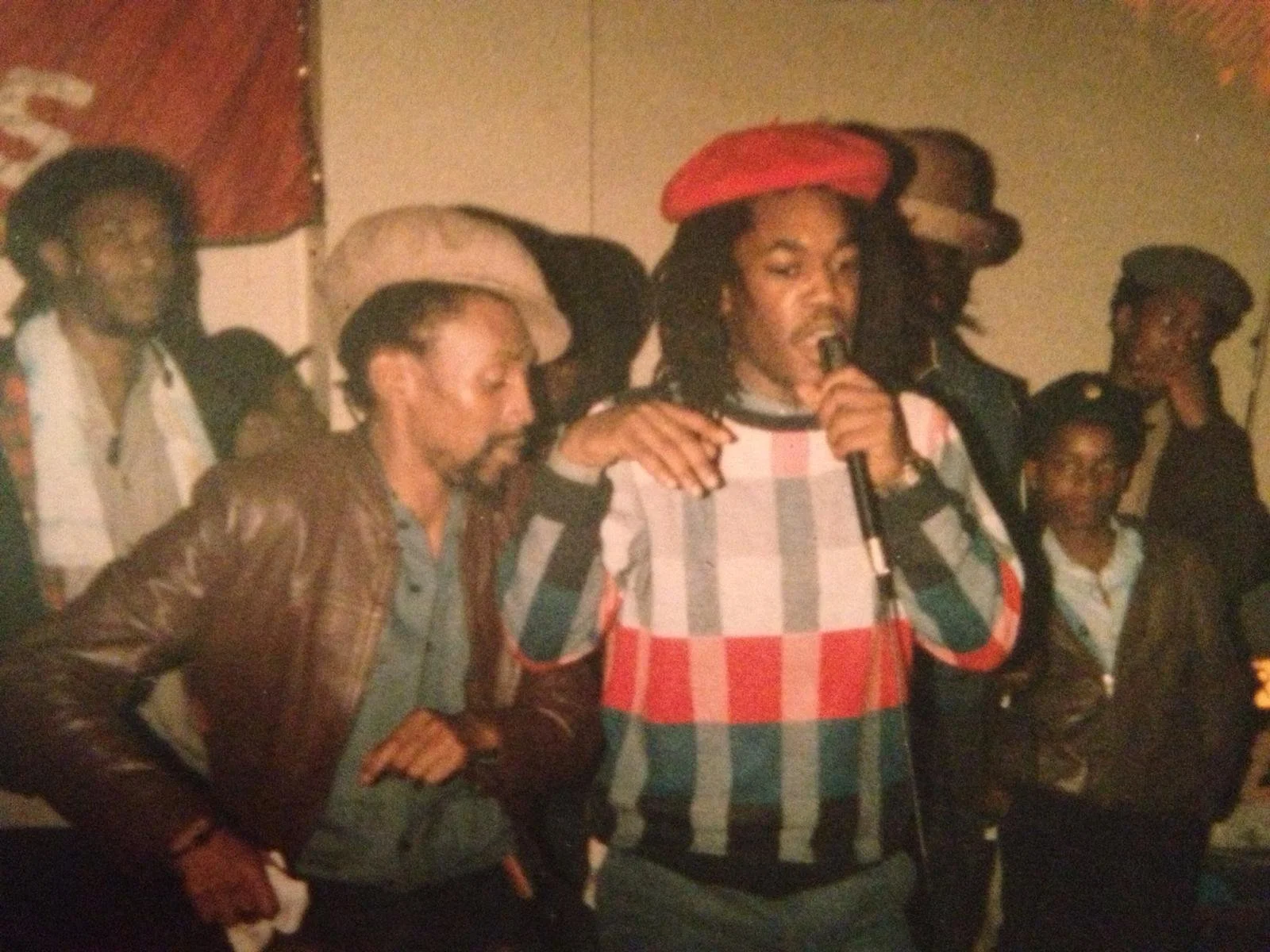

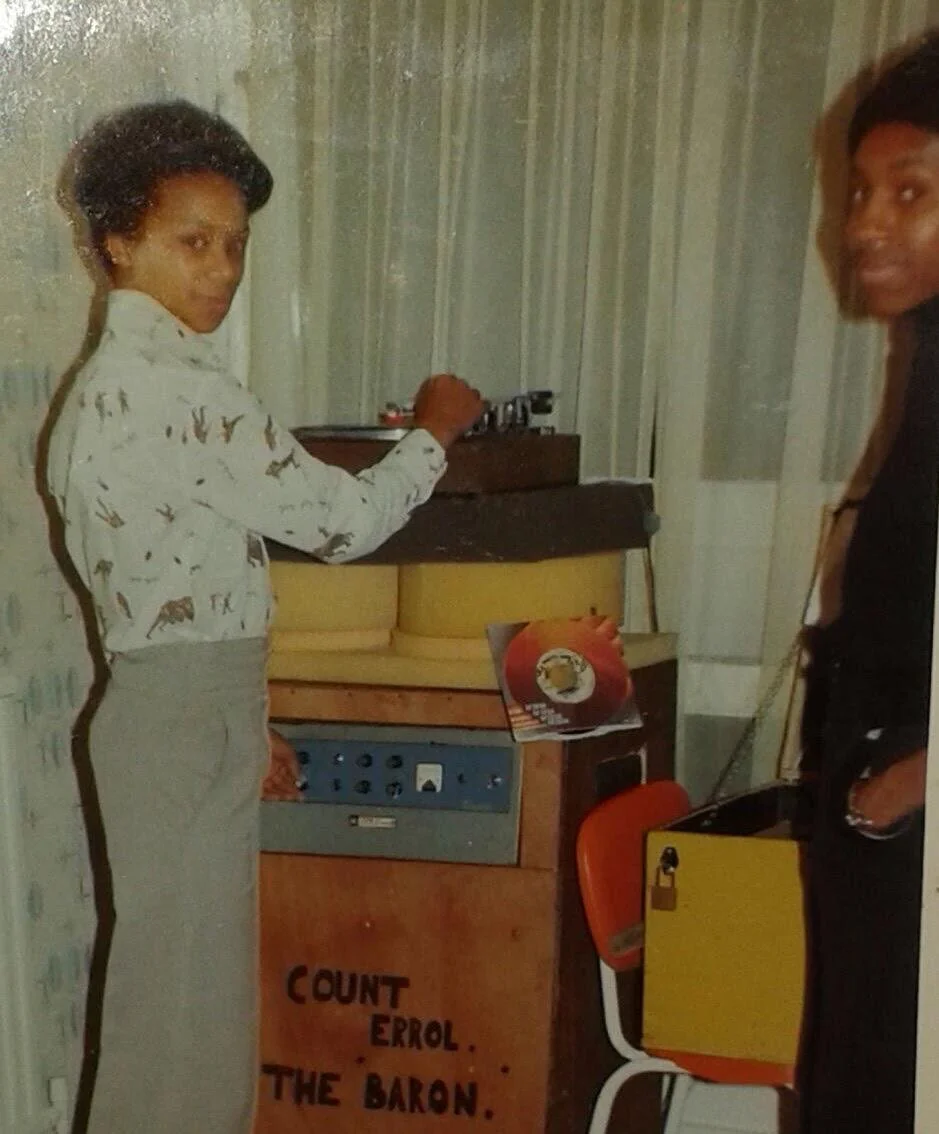

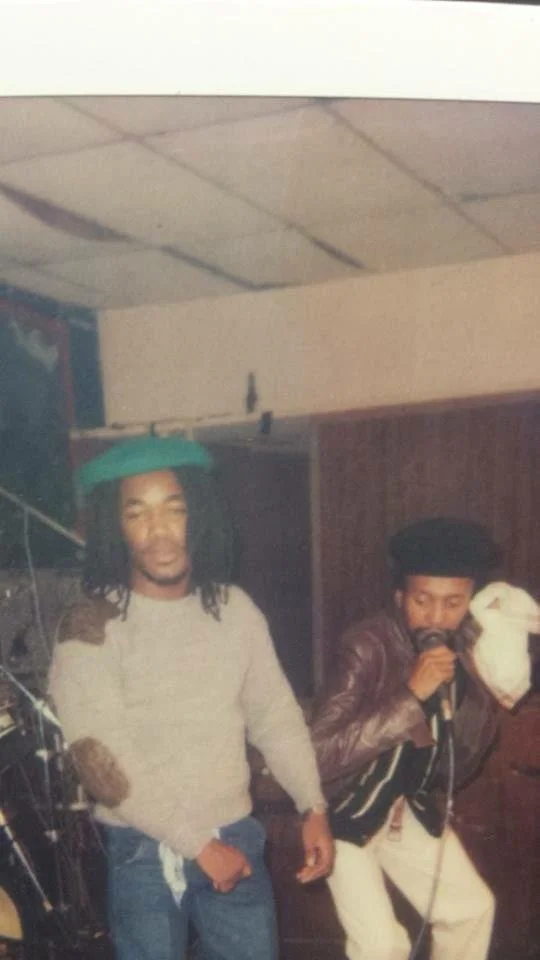

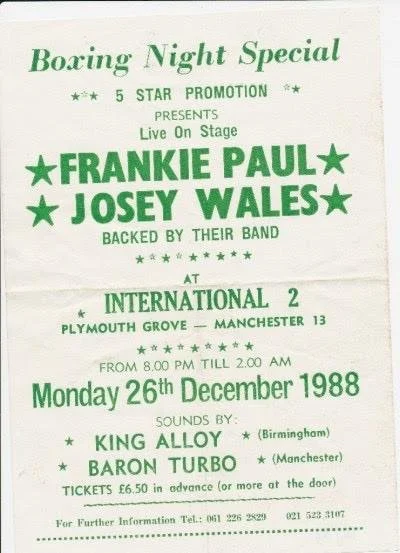

Baron Turbo, 80s. Images Supplied by Errol Beaumont.

Operating out of a compact and derelict flat in Hulme, Errol ‘Barzy’ Beaumont, Wizzy Dan, and Money Green, barely in their mid teens, built their first sound system by hand in 1974. Inspired by the first-generation Windrush immigrants they saw in their community running tunes from custom built systems, they pooled their hard-earned pocket money together and bought a 30-watt valve amplifier. Built from a combination of coarse sandalwood and gritty determination, ‘Baron Turbo Sound System’ were eager to graduate from a ‘youte sound’ into a local force to be reckoned with. Their set-up would broadcast the conscious sounds of reggae and dub to an adoring crowd of the local Caribbean community every week for years to come.

More than two decades earlier, on the 22nd June 1948, the HMS Windrush ship docked in Essex, bringing the arrival of the first group of immigrants from the West Indies. Whilst a large number settled in London, the stories of those who moved elsewhere are less documented. Manchester attracted many Windrush immigrants, many of whom found work in the docks, factories, and NHS. But these communities that settled in the areas of Hulme and Moss Side were segregated and isolated from the rest of the city, grappling with socio-economic issues and poverty, as well as disapproving sneers from those around them. Even today, Moss Side and Hulme are fabled in their notoriety, presented as ‘no-go areas’.

‘It was rough’ Errol recalls ‘We had cockroaches, mice, everything in our flat… the council dumped all the ethnic minorities in Hulme and Moss Side’. Unemployment in these areas during the 70s and 80s was rife, with some estimates at around 40%: ‘It was tough, because if you said your postcode, you wasn’t getting a job’. But despite, or maybe because of, the adversity they faced, tight knit pockets emerged which sowed the ground for the pulsing vibrations of reggae music, a story that is parallel to almost any city in the UK with a significant Caribbean population.

Sound systems became a crucial element of Caribbean life across the UK, as the first arrivals from the Windrush generation looked to export a slice of their culture to their new home. Pioneered in the 1950s by Jamaican ‘Sound Men’ such as Duke Vin and Lloyd Coxsone, sound systems blossomed in communities across London and soon, other cities. Illegal ‘Blues parties’ took place every weekend, colloquially named due to ‘Blue Beat records’ Ska tunes that you could expect to hear, powered by whichever sound system dominated in that area. Blues parties became a church of refuge for the Windrush generation and their children, a place to escape the harsh hostilities of prejudice that had negatively coloured their English experience. There was a spirituality that the weekly ritual stirred- blues parties offered an alternative to societal institutions that so often failed Black communities.

‘The school curriculum failed us. It didn’t teach us about our culture or Black history, so we had to educate the people ourselves.’ Wizzy Dan says. Not long after starting in 1974, Baron had their own nightly residency at Moss Side Youth Club, using their newfound platform and community status to play music that carried the resonant message of emancipation and liberation typical of Jamaican reggae records at the time: ‘When we started out, we’d play music by Burning Spear and Johnny Clarke, the message was always positive.’ It would be a labour of love, in their own words, that would continue for a lifetime.

In the early 1970s, the Sound System scene in Manchester was in its early development. The sounds being pushed by Manchester’s selectors and deejays were often not taken as seriously by their London or Birmingham counterparts, partially down to the comparatively small Caribbean community in the city. To London's Jamaican community, Northern England was considered a less significant and distant part of the UK diaspora, mockingly labelled as “country”. But despite being slightly behind the larger cities, the scene flowered throughout the 1970s, championed by systems such as Baron, President, Megatone, and Jah Guide, often competing directly against each other.

As Baron found their flow throughout the decade, they started to turn heads across England and even Jamaica: ‘They couldn’t ignore us just cos we were country’. Their sound was unique- the bass could knock the wind out of you, but their Hi-Fi amplifiers, although unconventional for the time, presented an immaculately clean sound. The newfound swagger and confidence in Moss Side’s dancehalls brought a status and respect within the community. As Money Green recalls “people I’d never met would stop me and shake my hand, and say yes my deejay.”

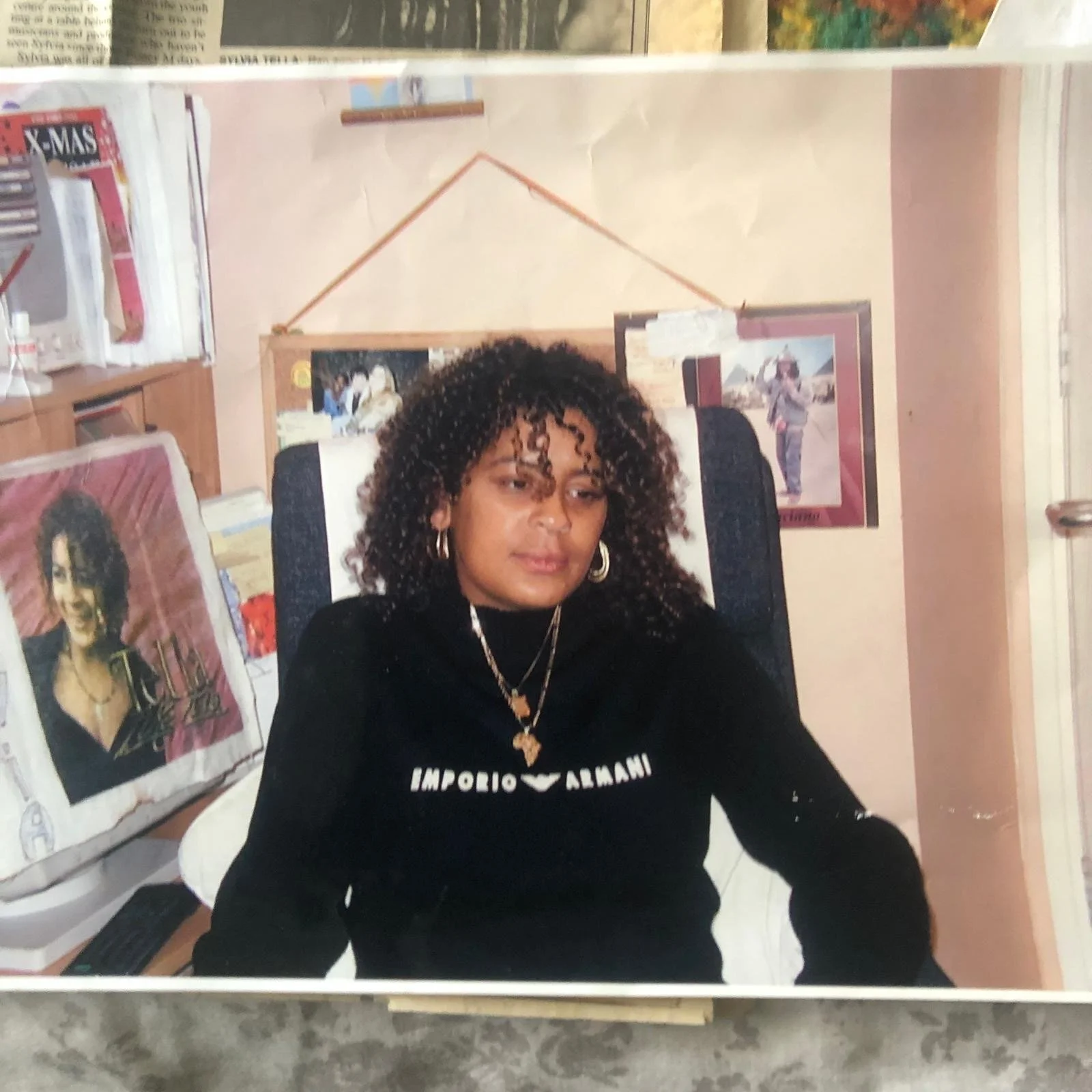

One of the many faces that frequented Barons dances was their classmate Sylvia Tella. After growing up in Cheetham Hill in a multiracial and ‘colourful’ community, she moved to Moss Side in her early teens. She recollects a misspent youth of school expulsions and car theft. But, like Baron Turbo, she found her purpose through music; bunking off school to queue up outside Marshes Records on Princess Road, keen to get her hands on the newest arrival of imported 7” reggae and soul records. A chance encounter whilst singing in a cabaret nightclub catapulted her career to celestial places outside of her teenage sphere of understanding. At 15 she was touring the world as a back-up singer for Boney M and singing on Top of the Pops. But she never forgot the formative experiences of her time in Manchester’s Black communities: ‘Manchester was my whole world, it was all I’d ever known. Even when I was touring the world, those streets never left me… I’m a street girl at heart’ she notes with a warm cackle. She has an entire portfolio of otherworldly stories from a life on the road, but it was Moss Side where she first cut her teeth and Manchester from which she attributes her success: ‘our community was so important, we were all inspired by each other and that moved us forward’.

For the people of Moss Side and Hulme, stepping out of the confines of their isolated corner of Manchester would expose them to the belligerent nature of the rest of the city. ‘We couldn’t step foot in town, we would get chased out. So we had to start our own thing,’ Errol remembers. Black Mancunians have told tales of club bouncers denying entry on account of having afro hair and being chased round the city centre by groups of violent skinheads. The National Front’s electoral prowess never reached the level many feared it would, but their snarling aggression on street patrols through Moss Side and Hulme posed a constant threat to the Black population, and an affirmation that their mere existence there was under constant duress.

Having a sound system meant being a particularly prominent target for the authorities: ‘you would have police raiding the blues, taking the weed so they could have a good smoke’ chuckles Wizzy Dan. And on the streets, police were abusing the 1824 Vagrancy Act, known as the ‘Sus Law’; using stop and search powers to indiscriminately harass young Black people. Lloyd Bradley writes that in the 1970s, police vans would cruise through Black areas like an ‘army of occupation’ searching young Black men on ‘utterly intangible suspicions.’ The situation reached its nadir by the latter half of the 1970s, and according to Bradley, almost every Black man in the country had negative experiences with the enforcements as a result of this law.

By 1980, the relationship between community and authority had deteriorated so badly, Errol remembers, that ‘the air was thick with tension’. Frustrated at the continuous abuse of power, a collective of musicians in Moss Side, known as Harlem Spirit, released the now anthemic reggae tune ‘Dem a Sus (In The Moss)’. The song’s lyrics tackled issues faced by the community, characterising their bubbling frustration at the continuous abuse of power on account of the Sus Law. In the 1980s, you could often hear it reverberating from blues parties in the community. Sylvia Tella sang with members of Harlem Spirit in an earlier iteration of the band called the Stimulators, but remembers the impact Dem a Sus had: ‘it was a Big tune.’ Dem a Sus was a call to arms, a reaffirmation that music remained the community’s greatest tool of resistance.

The dawn of the 1980s was marred by continued racial aggravation towards Black people across the country, and in 1981 tension boiled over into riots in almost every city with a strong Black community. Moss Side was no exception, and Wizzy Dan and Money Green were caught up. ‘We were protesting racism and showing our animosity towards the police’. Wizzy was cornered by a group of police officers who attacked him, beating him with batons and pulling his dreadlocks out of his hair. ‘I got punched in the eardrum, locks pulled out and all sorts. And then the police took me to court, trying to say that I attacked them’. The courts saw that Wizzy had been so badly brutalised that he won his case. With the payout, Baron opened a record store in Moss Side, refusing to be deterred from their lifestyle and determined to continue their journey of resistance. All they ever wanted was to unify their people against external hostility, with music at the core of their message.

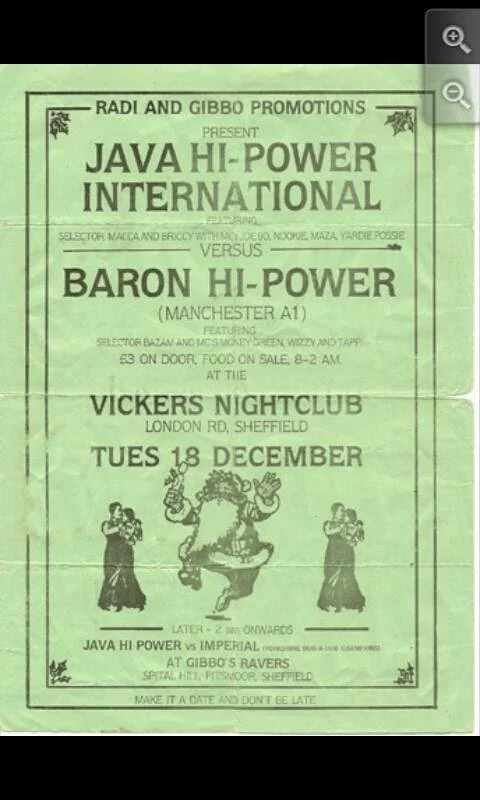

Flyers from 80s

Throughout the 1980s, Moss Side, like other Black areas of the UK, followed the evolution of reggae music. The dancehalls began to play the more soulful sounds of Lovers Rock, which made space for women to become the centrepiece, offering a breather from the usual overtly macho culture. Produced and sung entirely by organic British artists, ‘Lovers Rock was the first real Black British genre’ Sylvia recounts with a glistening grin. ‘And it was smoother, for the girls dem.’ Off the back of her illustrious career singing with Boney M, Steel Pulse and the Blow Monkeys, Sylvia continued to release and self-distribute her own Lovers Rock tunes. Iconic Jamaican reggae artists like Jackie Mittoo and Lloyd Chalmers played on her records, producing anthems like 1981’s ‘Spell’. Despite moving to London, she never forgot the Mancunian roots of her music. ‘Reggae really had a global impact from London, but in Manchester it meant so much to us. People supported us, they bought our records and they came to our shows.’ Perhaps the reggae scene of Moss Side and Hulme never quite reached the heights of London’s, but it provided meaning and solace to its residents. And, most importantly of all, according to Slyvia, ‘some fantastic memories.’

Baron Sound System today - Errol ‘Barzy’ Beaumont

Baron Sound system today - Money Green

Baron Sound system today - Wizzy Dan

It’s no exaggeration to say that without the culture created by sound systems, bass music today wouldn’t exist as we know it. Manchester boasts a rich spread of bass music icons like Nia Archives, Chunky, and the Hit and Run crew. Only because these original Mancunian pioneers of reggae and dub worked tirelessly to drive the culture forward, battling against social deprivation and vicious racism, do today's generation have a place to express themselves. So much is owed to Baron Turbo Soundsystem, Sylvia Tella, and their contemporaries, who stood tall in the face of adversity, and united their people through music. Their history doesn’t deserve to be excluded from Manchester’s music narrative. As Sylvia aptly summarises ‘we paved the way for the younger generation. Our whole industry has always been built off of supporting each other.’

Written by Finn Logue

Edited by Molly Clare & Zak Hardy