Designed by Dapper Dan: How the Original Hip-Hop Stylist Shaped Luxury Fashion.

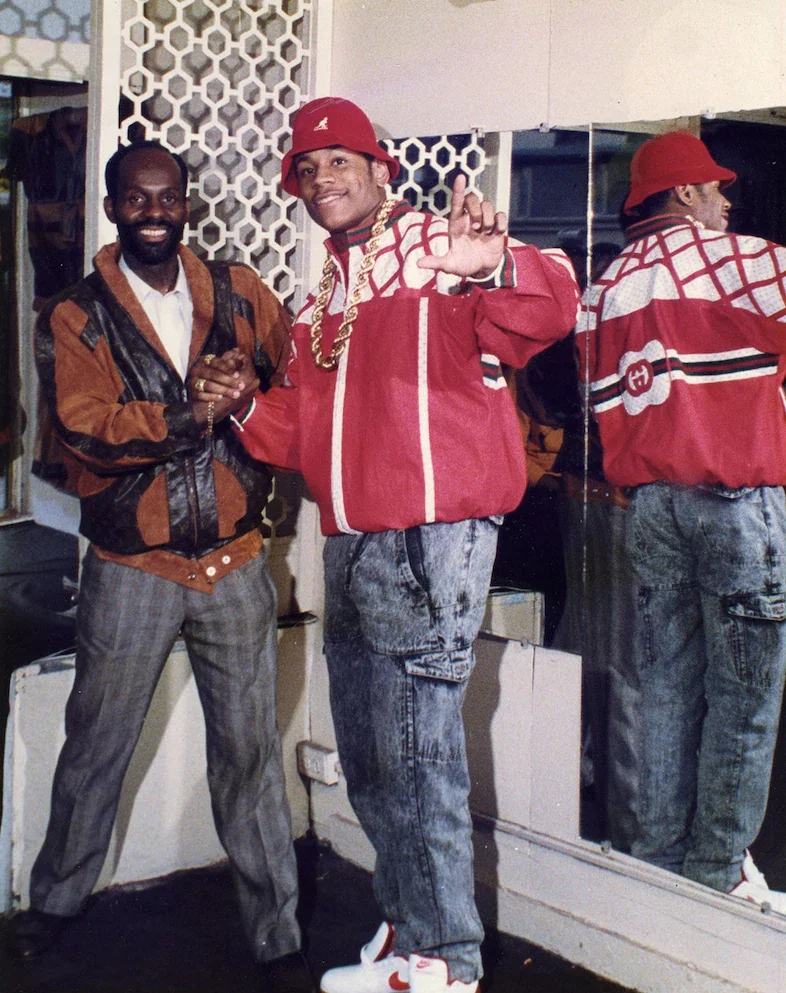

LL Cool J in a custom piece with Dapper Dan(on the left)

“86 was when the Bridge stuck together. The era of crack vials and Dapper Dan leathers" Cormega - The legacy

Streetwear was born out of the counter-cultural movements of the 1960s as a rejection of consumerism in favor of practical, often homemade clothing. Over the decades, subcultures like Punk, Skate, Surf, and most importantly, Hip-hop, have all embraced the DIY ethos of streetwear, bringing their own youthful flavors of resistance and rebellion.

Streetwear now dominates contemporary fashion, transcending its subcultural roots to become an ever-growing amalgamation of all things youth fashion. Streetwear makes up just over 10% of the global apparel and footwear market, generating over $185 billion in global sales. Walk down any UK high street and you’ll likely find retailers such as Urban Outfitters, Zara, or GAP, serving up the latest iteration of mass-produced “streetwear”. Luxury brands, whilst apprehensive at first, have also come to capitalize on the growing market. Since the late 2010s, consumers have been treated to a multitude of collaborations, including: Supreme X Louis Vuitton (2017), Palace X Ralph Lauren (2018), Dior X Stussy (2020), and Supreme X Burberry (2022).

The boundary between streetwear and haute couture has become increasingly blurred. This is strange when you consider the disparity between the cultures and values represented by the originators of streetwear, and the European luxury fashion houses. ‘Blurring the disparagement between classes should be perceived as a positive, yet luxury fashion’s appropriation of core streetwear values and its failure to acknowledge the attached cultural meanings are detrimental.’ Especially when they seek to profiteer off the very same marginalized communities they actively scorned, suppressed, and gave no acknowledgement to.

The relationship between high fashion and streetwear is more complex than simple narratives of appropriation and exploitation. To appreciate the full picture, we must first go back to Harlem, 1982, and a small boutique on 43 East 125th Street, between Madison and Fifth Avenues, known eponymously as Dapper Dan’s.

Throughout the mid-to-late '80s, Dapper Dan and his designs came to permeate hip-hop culture, cementing his status within hip-hop's golden age. Back in '82 though, Dap was just starting out, and hip-hop was in its infancy, considered by many to be ‘just a fad’ or ‘not even music’. Suffice it to say, rappers in the early ‘80s had little to no money, so simply couldn’t afford the wares retailed at Dapper Dan’s boutique.

Dap specialized in designing tailored fur garments, selling to a clientele that almost exclusively consisted of hustlers, drug dealers, and gangsters who were looking to flaunt their wealth. Having grown up in post war Harlem, Dap understood the allure of the hustler lifestyle. The fourth child of seven siblings, ‘Dap,’ christened Daniel R. Day grew up poor, both his parents having fled the Jim Crow South during the Great Migration in search of a better life, only to have their dreams dashed by racially motivated policies like redlining which led to disinvestment and a lack of opportunities. As a child, Daniel could clearly see the game was rigged. His father had to work three jobs just to put food on the table, while his mother raised him and his six siblings, a full-time job in its own right. Growing up in Harlem, Daniel had two primary sources of aspiration: the hustlers and the jazz musicians, both of whom were style icons. As a child, Daniel would sit with friends outside jazz venues like Count Basie’s Woodside Hotel, hoping to catch a glimpse of the musicians and their hustler patrons—and, more importantly, the outfits they sported: pinstriped suits, wide-brimmed hats worn at a tilt, shades, and zoot suits with baggy, larger-than-life silhouettes. ‘From an early age, Daniel understood that Black music had a sound and a look.’

Enjoy the article? Follow Dance Policy on Instagram for more.

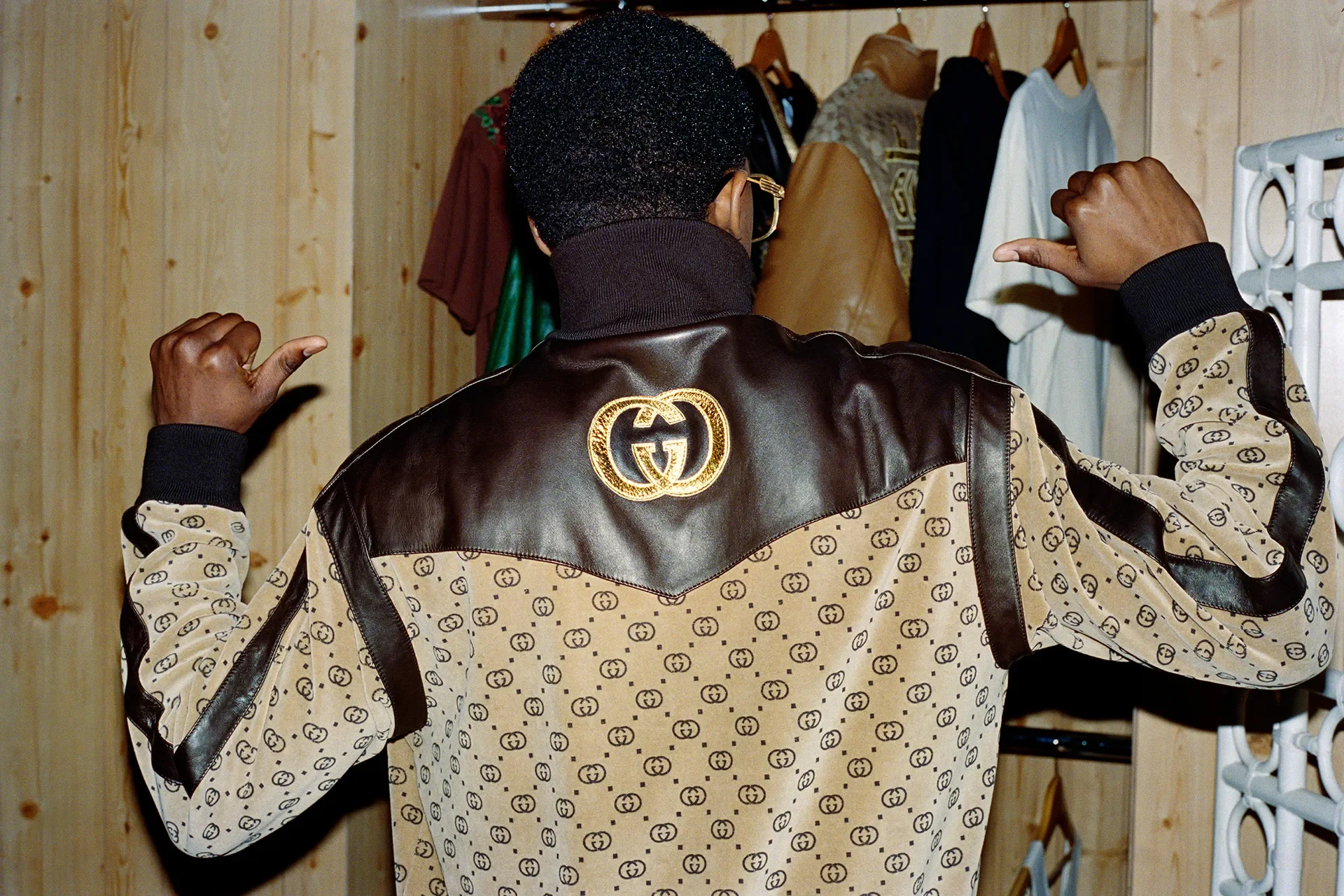

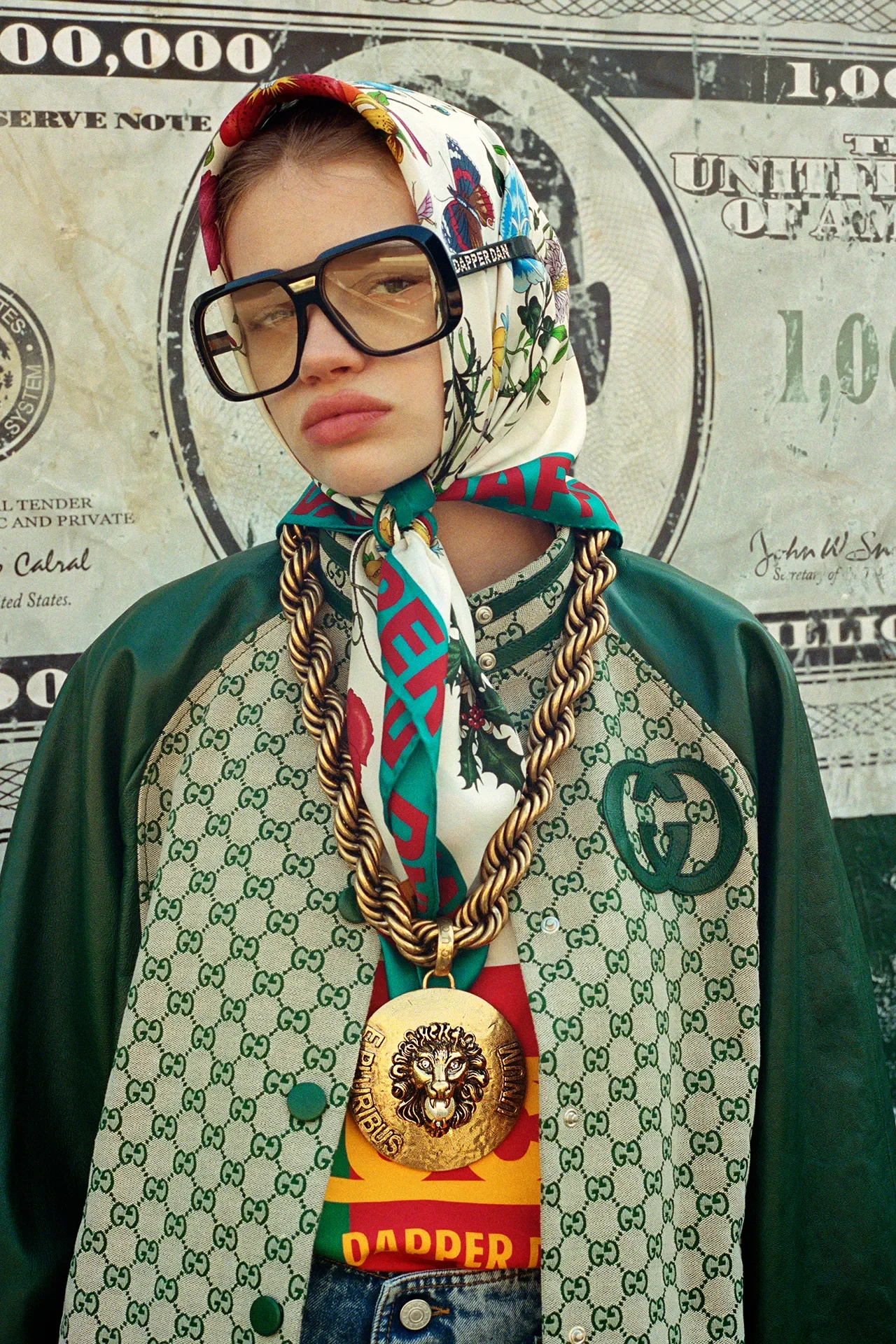

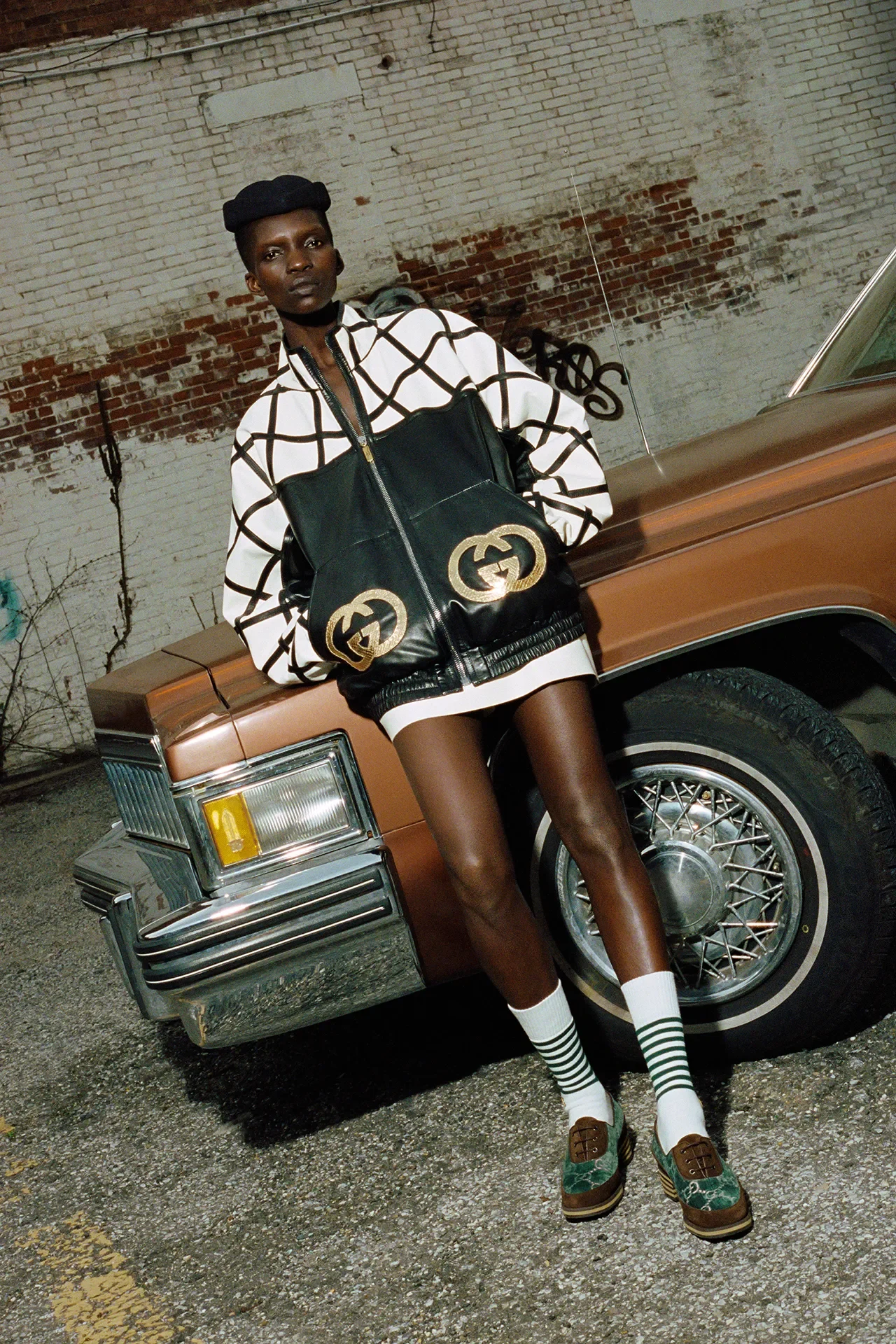

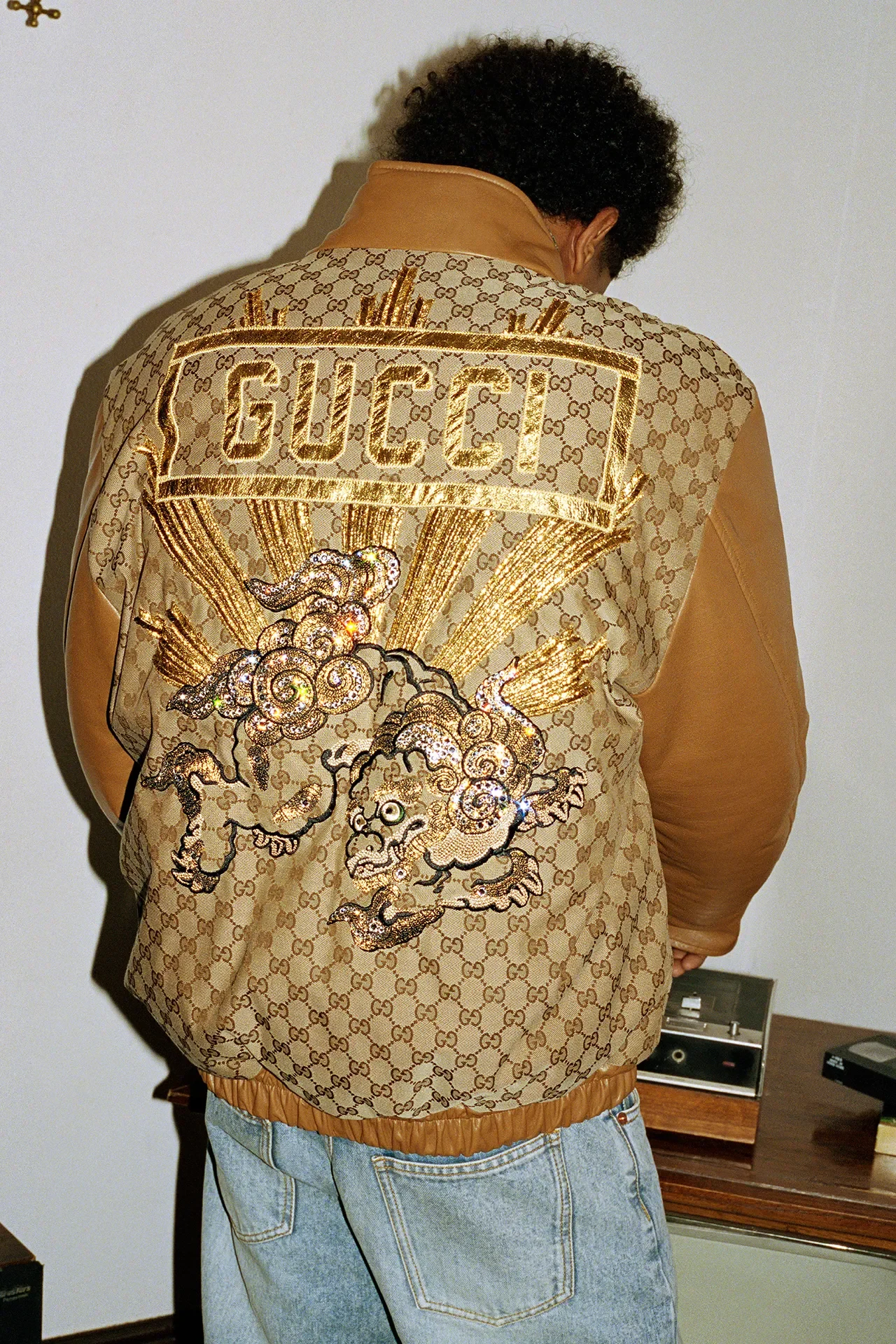

Dapper Dan’s first entry into the world of European luxury happened sometime in the early 1980s. Dap recalls how a young hustler named Little Man came by the boutique, accompanied by his girlfriend. Upon entering the store, all the customers began crowding around the young lady, fascinated by her little brown bag which was embossed and printed with a repeating LV monogram. At the time, European luxury fashion was relatively new to America. In New York, however, it was enjoying a surge in popularity as a signifier of status, thanks to the success of Wall Street and the cocaine trade. Almost immediately, Dap was struck by an idea and turned to Little Man: “You excited by a little bag? Imagine if you had a whole jacket.” And so, this chance encounter birthed Logomania, an entire movement that continues to influence fashion to this day. In the years to come, Dap would design garments featuring the logos of Gucci, Louis Vuitton, Fendi, Versace and MCM.

The olympian Diane Dixon in 1989, wearing Dapper Dan.

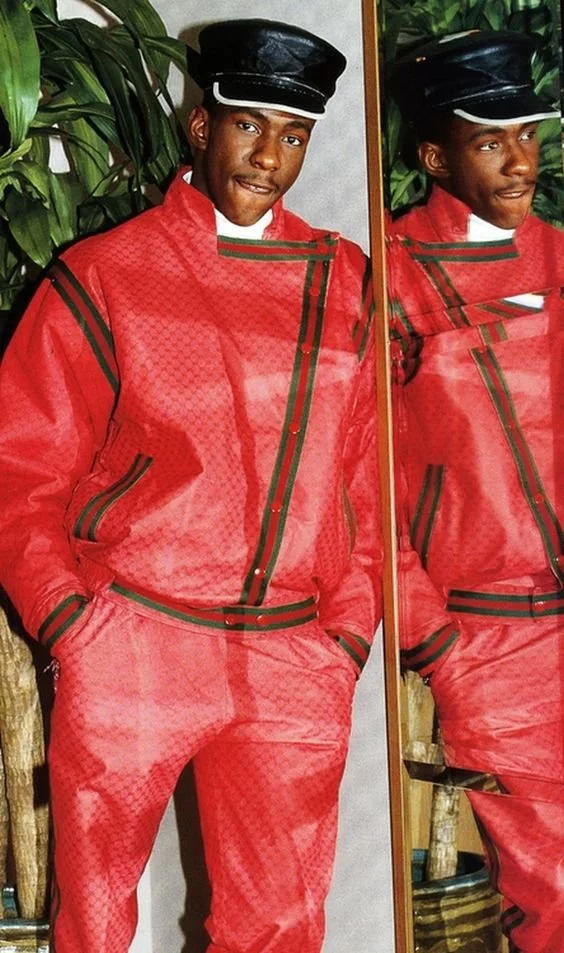

Bobby Brown in a Dapper Dan’s Gucci suit

To the uninformed, Dapper Dan’s designs may have been dismissed as knockoffs, but that couldn’t be further from the truth. The majority of the luxury brands Dap was referencing made luggage, not clothes. Fendi only started selling menswear in 1990, Louis Vuitton wouldn’t launch ready-to-wear clothing until the late ‘90s, and MCM debuted its first clothing collection in 2017. Because of this, Dap was an innovator when it came to printing logos onto leather clothing. Unlike a bag, the designs had to move with the body and still look and feel like high-quality garments. To do this, he studied textiles and attended trade shows, always ensuring he was at the cutting edge of technology. Dap’s designs were so influential that the heritage brands ended up stealing his work. While Dapper Dan blatantly incorporated the symbolism of luxury fashion into his designs, he ‘never knocked them off, he knocked them up’.

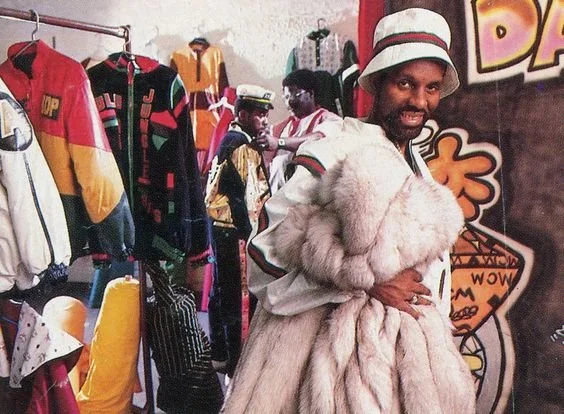

In the early days of hip-hop, rappers took fashion inspiration from the hustlers. Two of Dap’s first rapper clients, Jam-Master Jay and Rakim, were introduced to the boutique through hustler friends. With hip-hop's rich history of sampling and rebellious creativity, it’s no surprise that Dapper Dan’s designs became so popular among New York's rap artists. In the 1980s, the budgets for hip-hop albums were relatively small. Most artists would only make one music video per album and had a limited wardrobe allowance, so the clothing would be used for album covers, videos, and promotional material. Wanting to be captured wearing something unique, many of the artists looked to Dapper Dan to design custom outfits for their albums. Consequently, during hip-hop’s golden era, Dapper Dan thoroughly saturated the culture, designing outfits for Erik B & Rakim, LL Cool J, Salt-N-Pepa, The Real Roxanne, Big Daddy Kane, Sparky D, and Roxanne Shante, to name but a few.

Salt-N-Pepa in their jackets designed by Dapper Dan and Christopher Martin.

By 1988, mainstream culture was beginning to understand and accept hip-hop for the art form it is, exemplified by the launch of MTV’s new Saturday morning show Yo! MTV Raps. Thanks to the show, hip-hop was reaching a wider, international audience, and so was Dapper Dan. Sadly, with fame came notoriety. Concerned with the dissemination of their symbols among a young, Black, working class, the European houses would come to crack down on Dapper Dan with raids, seizures, and court orders. The European houses were worried that an association to Black people would de-value their brands. Perhaps even more insidiously, Tommy Hilfiger, seeing the market potential of hip-hop culture and its popularity amongst a predominantly White American youth, threatened to withdraw advertising revenue from the MTV network unless images of Dapper Dan designs were blurred on broadcasts of Yo! MTV Raps. Having been effectively forced underground, aspirational American apparel brands like Tommy Hilfiger and Ralph Lauren were quick to fill the void, catering to the more preppy hip-hop look. With the success of Tommy and Polo Sport, the European fashion houses would eventually follow suit, appropriating swathes of Dapper Dan’s looks in the process.

In 1992, after almost ten straight years of operating twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, Dapper Dan’s Boutique closed its doors for good. The final nail in the coffin came when Fendi and their lawyers placed an injunction on the boutique, allowing them to seize over a quarter of a million dollars worth of stock and machinery. Feeling dejected and defeated Dap entered into one of the darkest periods of his life, the once energetic and charismatic designer spent the next three months bed-ridden, falling behind on his mortgage and almost losing his house. Alone with his thoughts Dap had the chance to evaluate what had gone wrong. Seemingly, everything had started falling apart shortly after his designs had entered the mainstream, a White world that wanted his designs but not the designer. Dap may have been down, but he definitely wasn’t out, through his stupor he devised his comeback, This time Dapper Dan would stay underground.

Over the next several years, on a shoestring budget, Dap, accompanied by his devoted wife June would sell mass produced goods like printed T-shirts and skirts from a table on 125th Street alongside other street vendors. The very same street where Dap owned his three storey boutique only a few years ago. In the mid 90’ Harlem was undergoing a new wave of gentrification. The war on drugs alongside years of economic and social neglect had forced many Black communities out of Harlem, clearing the way for developers to buy up cheap lots of inner city real-estate. With white investment, came the de-stigmatization of Harlem and an increase in ‘Ghetto Tourism‘. Dap recalls days while working as a street vendor where bus after bus of European tourists would pile out onto 125th Street, browse his wares, and then jump back on the coach without making a purchase, continuing their voyeuristic tour of Harlem.

Photo of Dapper Dans Boutique

Dapper Dan in his shop. The two of the jackets on the left were custom-made for Boogie Down Productions and The Jungle Brothers,1989

Having faced the demoralisation of selling his clothes as a street vendor, Dap took to the roads, spending most of the 1990s travelling to cities and states as far flung as Florida, Detroit, Chicago, and Atlanta. His relentless work not only allowed him to rebuild his brand in a controlled way, but also to experience first hand the similarities and differences in Black communities across America, many of which had been traumatised by the state-sponsored war on drugs.

Towards the end of the 1990s Dap heard a knock at his door. He had been running his manufacturing from the ground floor of his apartment with a few trusted tailors. Dap opened the door to find Ghostface Killah’ stylist, who’d been tasked by the rapper to track down Dapper Dan so he could create a wardrobe for some of his upcoming music videos. Dap would continue to make custom outfits for the rest of the Wu-Tang Clan as well as Aaliyah, G.Dep, Nelly, and Busta Rhymes, becoming one of rap's best kept secrets of the early 2000’.

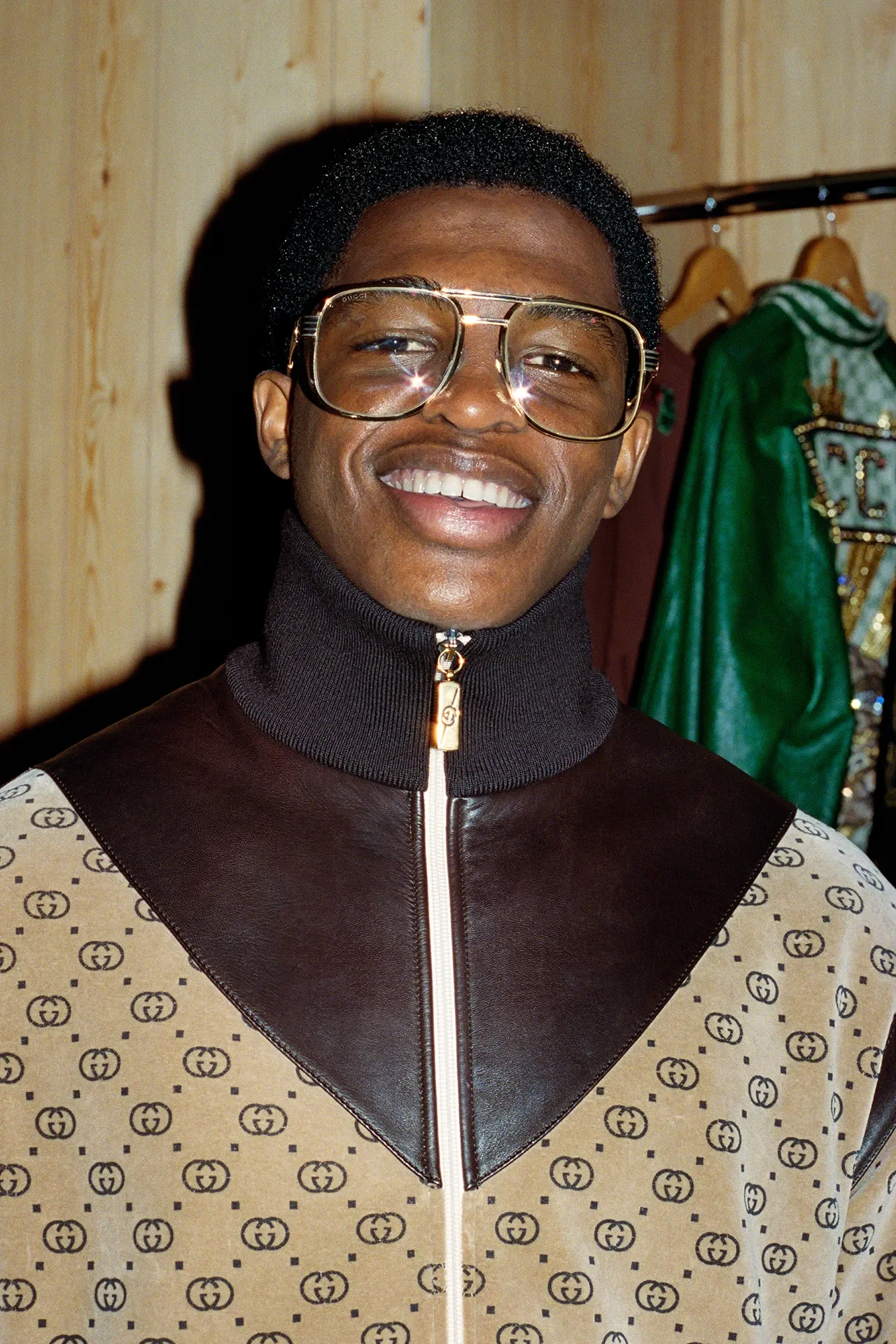

Whilst Dapper Dan was enjoying an underground resurgence, other Black owned brands like FUBU, Phat Farm, and Karl Kani were beginnng to struggle. In their place the European Heritage brands were poised to dominate the high-end hip-hop market, stealing Dapper Dan designs to exploit the cultural capital Dap had inadvertently built for them. Brands like Louis Vuitton, Fendi, Gucci, and Versace would continue to appropriate Dap’s work for years, receiving little to no backlash. However, that all changed in 2017 when the creative director of Gucci, Alessandro Michele “referenced” a balloon sleeved bomber jacket designed for olympian Diane Dixon without crediting Dapper Dan. Black Twitter was outraged and, spearheaded by Dixon herself, demanded a full apology and acknowledgement. Gucci decided to go one step further and offered Dapper Dan a partnership.

This was not the first time Dapper Dan had been offered a job at a major label, having previously turned down Tommy Hilfiger. The job at Gucci was different though. Gucci offered the chance to collaborate as a fully credited designer, rather than simply an employment opportunity. Dapper Dan accepted the Gucci deal, a decision that wasn’t met by all with immediate approval. Having spent the best part of three decades subverting and recontextualising luxury symbols, his decision to join forces with those he seemingly opposed appeared to be at odds with his ethos. Equally, given European luxuries track record of suppressing people of colour, some feared that Gucci were simply trying to legitimise their appropriation of Hip-hop culture through tokenist gestures.

Fully aware of his positionality within the world of luxury fashion, Dapper Dan approached the offer with caution, challenging Gucci to come to Harlem so they could speak face-to-face. To Dap’ astonishment, Gucci were happy to oblige, and even improved the initial deal, offering to create a limited Gucci-Dapper Dan Collection and open a Gucci - Dapper Dan studio where Dap could continue creating customised looks with Gucci’ full endorsement. By coming to Harlem and opening the Dapper Dan Atelier, Gucci gave full recognition to Black Luxury and one of its originators. Dapper Dan speaks of building a ‘Black Staircase’ for Black fashion, paving the way for other Black designers to follow his blueprint. With a few notable exceptions, luxury fashion is still very much a White space, owing to foundations built upon colonialism and structural racism which persists within the industry. Dapper Dan’s appointment at Gucci created a seat at the table of a White industry and an opportunity to foster systematic change from the inside, the legacy of which is still being determined.

Words by Joe Charles

Edited by Zak Hardy