What is Driving The Dance Music Boycott for Palestine?

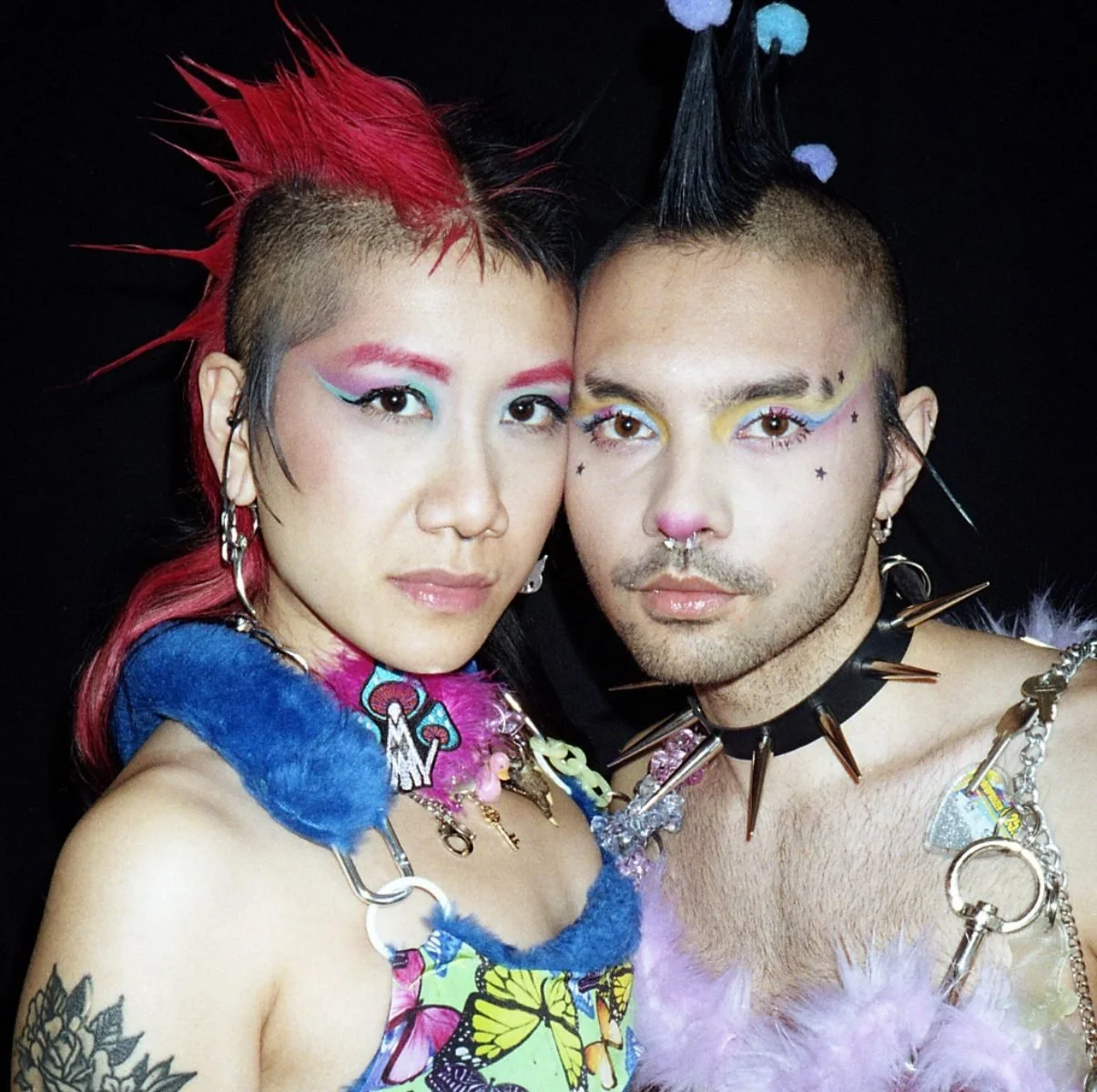

Following the movement of artists that have withdrawn from Boiler Room, Sónar, SXSW and Field Day, we spoke with Scottish artist Magnus Westwell and Rotterdam-based electronic duo Animistic Beliefs who have been vocal about their position to boycott. Photo taken by Ryan Ashcroft on his visit to Palestine, 2017.

‘We were together, and they shot at us at once’ says Abduallah al-Haddad, who was 200 meters from the US-Israeli Gaza Humanitarian Foundation (GHF) site when an Israeli tank began firing at Palestinians.

Aside from the few with eSims, most Gazans have lost all connection to the internet that had previously allowed them to broadcast these crimes against humanity in real time. After Israel had destroyed the last remaining fibre optic cable within the region, while proceeding to target and assassinate journalists both within Gaza and as far as Lebanon, we are provided with very limited insight into the scale of violence that the genocide continues to provoke.

With the West not only stubbornly upholding relations but actively coordinating Israel’s war crimes, there has been a sense of urgency to disentangle the financial ties that help facilitate the genocide, particularly within Dance Music. But when we talk about this back and forth about who decides to perform on SXSW, Boiler Room, Sónar and Field Day, it is hard to not see it as something that is entirely removed from the brutal reality that Palestinians continue to face on the ground.

“I think art holds the power to either legitimise violence or resist it and choosing where and how we show our work is a form of political agency” – Magnus Westwell

Photo taken by Ryan Ashcroft

Nevertheless, Israel has always relied on its cultural clout. From competing in Eurovision to Tel Aviv inserting itself as a major export for global dance music that Boiler Room has since deleted the coverage of, this attempt to normalize themselves as cultural actors in turn helps to legitimize their political violence as something that is beyond reproach.

And as more and more major dance music platforms get acquired by KKR – the private equity firm that has investments in Israeli weapon manufacturers, defence contractors, and settlements – people have been quick to identify companies like Boiler Room as economically entangled with the ongoing genocide.

But does the buck stop at just refusing to go to certain event spaces subsidized by KKR? Given the enormity of these firms and the unfathomable scale of the genocide, can we really say that our absence at these spaces is enough to even alleviate an iota of suffering in the besieged Gazan enclave, that is currently bearing the brunt of a famine? To some, it might seem like the bare minimum.

Yet in spite of this, we have found that even this push to boycott these platforms is not always unanimously met with support. Although the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (PACBI) welcomed Boiler Room’s statement that addresses its acquisition by KKR (emphasising their ‘unapologetically pro-Palestine’ stance despite making no pledge to withdraw from KKR), many were left conflicted.

Some defended Boiler Room on the basis that they cannot control who they are acquired by, with artists like Ben UFO going as far as to say that we should in fact be ‘defending one of the only platforms in our world that still have the potential to launch careers.’

Photos taken by Ryan Ashcroft on his visit to Palestine, 2017.

Others, on the other hand, saw it as a complete betrayal of the grassroot scenes that they had previously platformed—not excluding its coverage of the Palestinian hip-hop and electronic underground scene, that helped cast an international spotlight on artists such as Al Nather and Sama’ Abdulhadi.

Those who refuse to boycott Boiler Room must contend with the fact that they continue to collaborate with other festivals that have also been acquired by KKR, such as Sónar, where they had setup a dedicated main stage despite PACBI actively advising festivalgoers to not go to Sónar.

This begs the question, was Boiler Room’s lip service simply that—lip service incapable of realizing true Palestinian solidarity? Or is it simply the case that these platforms will need to make moral concessions for them to be financially viable. What then, are we really hoping to achieve through this tireless commitment to boycott these festivals? Can it legitimately disempower the private equities subsidising them, and if so, what kind of spaces can emerge from the ashes?

For many artists it becomes a lot less feasible for them to do their work once they are alienated from the larger music industry – with Ravers for Palestine having previously launched Strike Funds to cover the fees of artists who had lost paid work due to their commitment to boycott SXSW before. What will allow us then, to shape a sustainable alternative for these artists who do take a stand?

“We would love to play in spaces where ethics aren’t just aesthetic. Where solidarity and community are real, not symbolic or trendy words” - Animistic Beliefs

As we try to grapple with the atrocities that are enacted in Gaza and the occupied West Bank day in and day out, mainstream media outlets and politicians have tried to obfuscate this through their suppression of pro-Palestinian movements and artists; with sensationalist reporting targeting Kneecap and Bob Vylan more recently, as well as Palestinian Action being proscribed as a terrorist organisation—while Israel gets to carry on terrorizing the lives of Palestinians with total impunity.

To pierce through the discord, we spoke with some of the more vocal musicians who have pulled out of these festivals – that have since been exposed for their ties in either genocidally complicit governments or companies – to recap on what has underpinned these boycott movements over the past couple of months.

Magnus Westwell, the Scottish artist, choreographer and composer dropped out of SXSW after a report was leaked on X that former Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron, and Labour’s former Prime Minister Tony Blair, along with Labour Friends of Israel member Peter Kyle, would be participating in the festival through a number of panel discussions and workshops that they were running. We spoke with Westwell to dive deeper into what has motivated them to commit to their withdrawal from SXSW and ask in what way their political conviction relates to their creative practices.

We also spoke with the electronic Rotterdam-based duo Animistic Beliefs, consisting of Linh Luu and Marvin Lalihatu, to gain more insight behind what challenges they faced dropping out of Sónar, and what kind of future they think this broader movement to challenge KKR, and private equity alike will provoke within the wider music industry.

MAGNUS WESTWELL / SXSW

How did the decision to pull out of SXSW come about—did it take a lot of deliberation or was it a simple choice to make?

I had always felt conflicted in taking part in the festival, initially due to the performance fees that were well below industry standards, and knowledge of their previous associations with the US military. Corporate platforms like SXSW are often propped up by capitalist systems that rely on exploitation. When those same systems are tied to military funding or governments complicit in genocide, we have to see the connections clearly.

During the week of the festival, having realised that SXSW were secretly platforming politicians - responsible for state violence resulting in hundreds of thousands of civilian deaths in Iraq and UK government complicity in the genocide in Gaza - it was then an obvious decision to step back and join the boycott.

These platforms operate as part of a wider system that launders war crimes through art and entertainment. I couldn't allow my work to be used in that way.

Do you feel there are limited spaces available for artists – who may otherwise be financially struggling – to find a platform that can both launch their careers without having to make some kind of moral concession?

I question whether SXSW London offered much for the artists involved - in the end it felt like the festival was benefitting from the programmed artists much more than the artists would be benefitting from the festival. One way to show that they respected artists would be to pay a fair fee.

I’m much more interested in gradual, sustainable growth in a career that upholds the ethical practices that are integral to the art I make. There are so many incredible grassroots and community venues and festivals in the UK that uphold strong ethical practices and are committed to supporting young, emerging artists, whilst also paying artists fairly. I believe these spaces offer a lot more to artists than corporate entities like SXSW. We need to refuse to allow exploitative institutions like SXSW to define our worth or trajectory as artists.

Does the ethos of your sound and performance art inform the politics behind your decision to pull out of the festival?

I create work to encourage collective experiences of empathy and vulnerability – for people to feel emotions, to feel alive, and to connect to themselves, each other and the world around them. I feel that we are often left to pick up the pieces from decisions made by those in power. We are all complicit, but we have to do what we can to force those in power within organisations and governments to act. I think art holds the power to either legitimise violence or resist it and choosing where and how we show our work is a form of political agency.

ANIMISTIC BELIEFS / Sónar.

Has your decision to withdraw from Sónar helped you to connect with other artists who have also committed to the boycott, or have you received any pushback at all?

Yes, both. We’ve had some really powerful conversations with close friends who also chose to cancel, but also with artists we hadn’t spoken to before, who told us our stance gave them the push to speak out in their own way. That sense of connection and shared refusal has meant a lot! In general, I can see it made a very positive impact.

There’s been pushback too, although very little. A lot of people are fearful, and that fear manifests in different ways. Some disagree with our tactics and insist there are “better” ways to respond, which often just means staying complicit or quiet.

Some are so uncomfortable with refusal that they project the disruption onto us. As if we’re the problem. As if we’re the ones trying to end festivals. But it’s private equity that’s turning culture into a financial product and destroying everything that made these scenes worth building in the first place.

Fisher would call that mindset internalization of capitalist realism, where the imagination is so colonized that even resistance feels threatening. Despite all that, we know we did the right thing and so did many others before and after us! We’re proud of the ripple effect it's had!

Are there any other festivals or spaces that you'll be performing or attending this summer that have alternatively helped champion the Palestinian cause?

Honestly, right now, we are in survival mode. We had planned for a big summer, but that changed when we made the decision to pull out of all KKR events.

In the past, we survived by balancing community-based gigs with bigger, better-paid festivals. Most grassroots spaces don’t have much budget, and we’ve always been happy to play them because that’s where we feel at home. But to sustain ourselves, we relied on the larger bookings. That entire structure shifted once we spoke out. That’s the cost of taking a stand!

So now we’re in a different position. It would mean a lot to see festivals extend solidarity not just to Palestine, but also to the artists who refuse to stay silent.

We would love to play in spaces where ethics aren’t just aesthetic. Where solidarity and community are real, not symbolic or trendy words.

What kind of ripple effect do you think this push to boycott festivals or other platforms owned by KKR has on the wider music industry?

You can already feel the shift. Some festivals have been forced to say something, even if it’s vague or misleading. That shows the pressure works. But more than that, it’s opened up a deeper conversation. About ownership. About complicity. About what we actually want culture to be. People are asking questions they weren’t asking before. That’s where change begins!

Words by Reda Gray

Photos of Palestine provided by Ryan Ashcroft.

Special thank you to Magnus Caswell and Animistic Beliefs for agreeing to the interview.